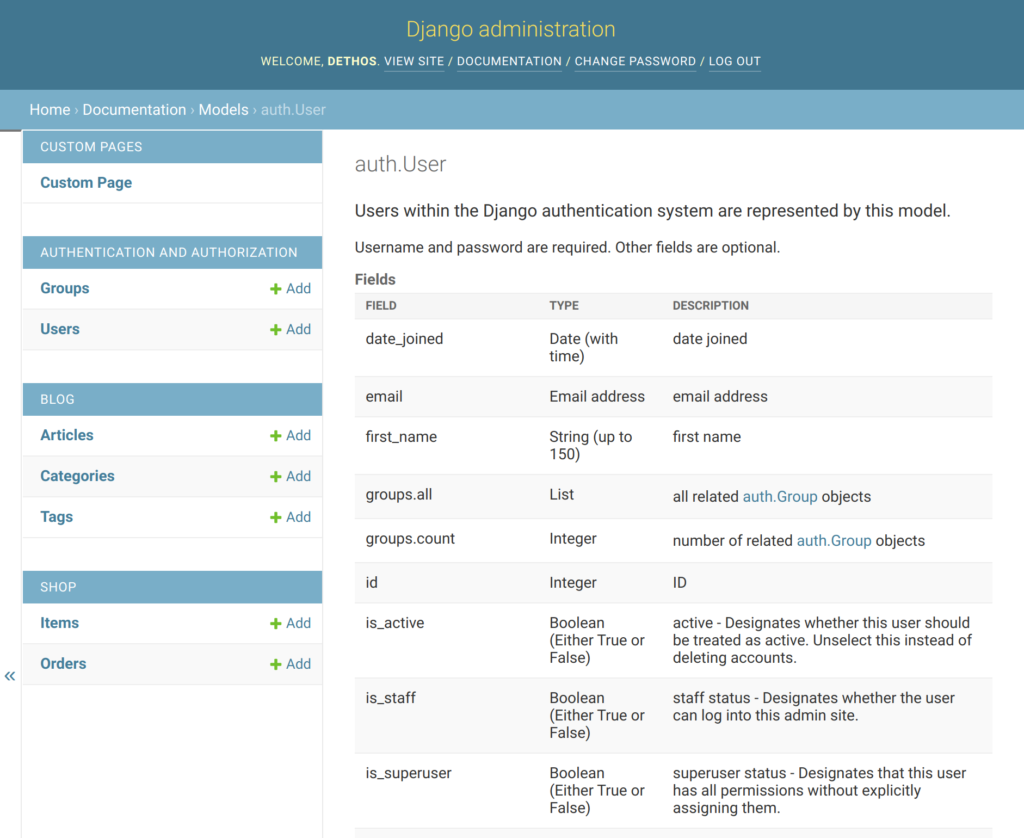

Reporting application errors to a (small) list of admins is a feature that already comes built in and ready to use in Django.

You just need to configure the ADMINS setting and have the application ready to send emails. All application errors (status 500 and above) will trigger a new message containing all the details, including a traceback.

However, this message can contain sensitive contents (passwords, credit cards, PII, etc.). So, Django also provides a couple of decorators that allow you to hide/scrub the sensitive stuff that might be stored in variables or in the body of the request itself.

These decorators are called @sensitive_variables() and @sensitive_post_parameters(). The correct usage of both of them is described in more detail here.

With the above information, this article could be done. Just use the decorators correctly and extensively, and you won’t leak user’s sensitive content to your staff or to any entity that handles those error reports.

Unfortunately, it isn’t that simple. Because lately, I don’t remember working in a project that uses Django’s default error reporting. A team usually needs a better way to track and manage these errors, and most teams resort to other tools.

Filtering sensitive content in Sentry

Since Sentry is my go-to tool for handling application errors, in the rest of this post, I will explore how to make sure sensitive data doesn’t reach Sentry’s servers.

Sentry is open-source, so you can run it on your infrastructure, but they also offer a hosted version if you want to avoid having the trouble of running it yourself.

To ensure that sensitive data is not leaked or stored where it shouldn’t, Sentry offers 3 solutions:

- Scrub things on the SDK, before sending the event.

- Scrub things when the event is received by the server, so it is not stored.

- Intercept the event in transit and scrub the sensitive data before forwarding it.

In my humble opinion, only the first approach is acceptable. Perhaps there are scenarios where there is no choice but to use one of the others; however, I will focus on the first.

The first thing that needs to be done is to initiate the SDK, correctly and explicitly:

sentry_sdk.init(

dsn="<your dsn here>",

send_default_pii=False

)This will ensure that certain types of personal information are not sent to the server. Furthermore, by default certain stuff is already filtered, as we can see in the following example:

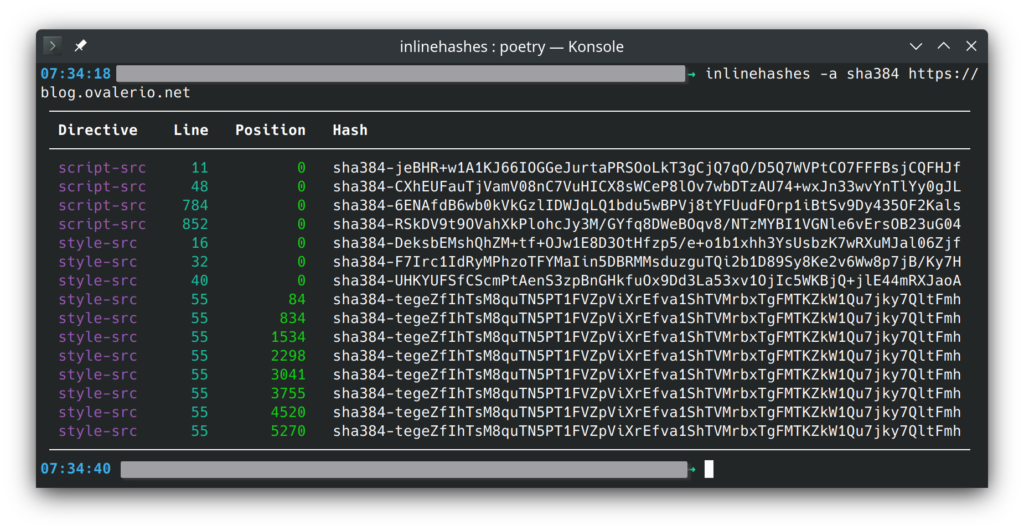

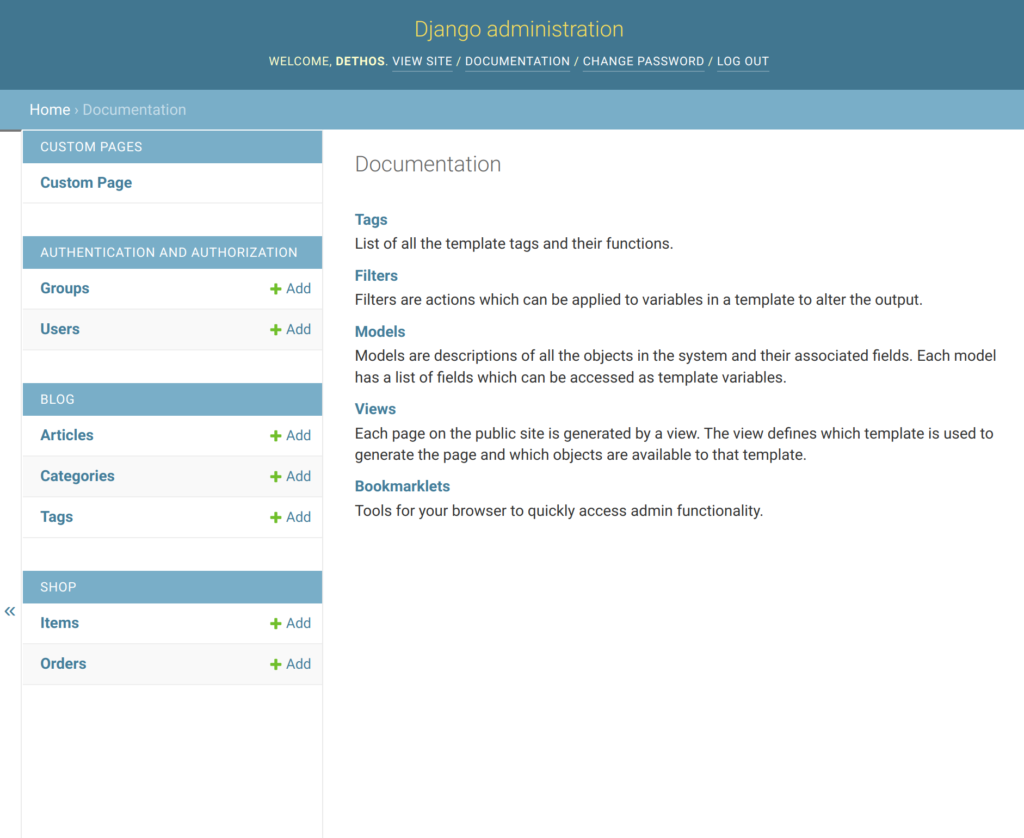

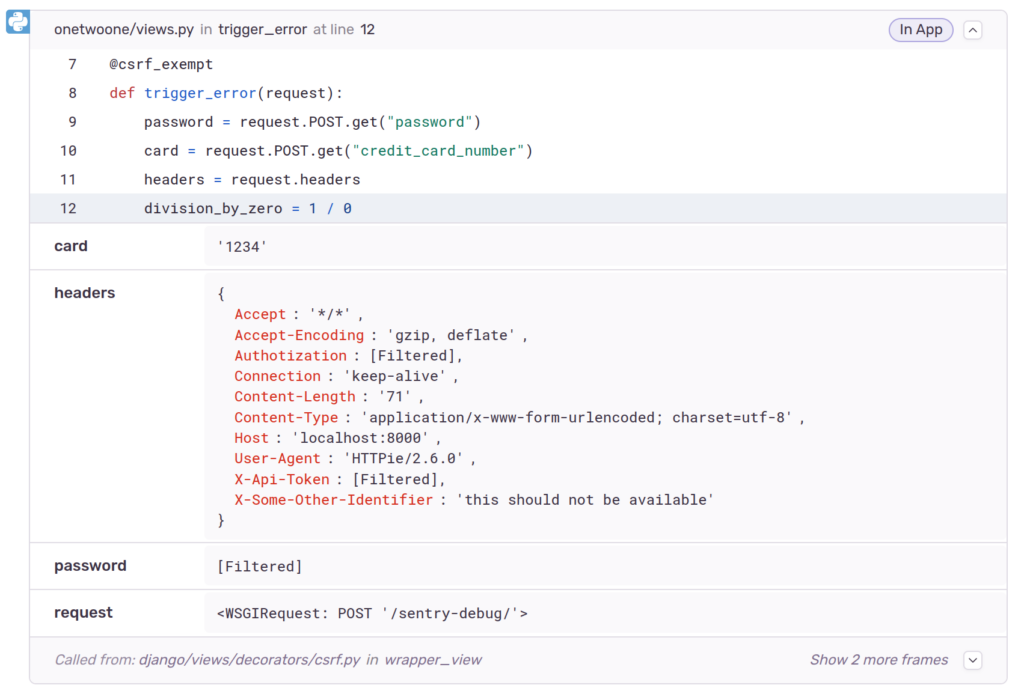

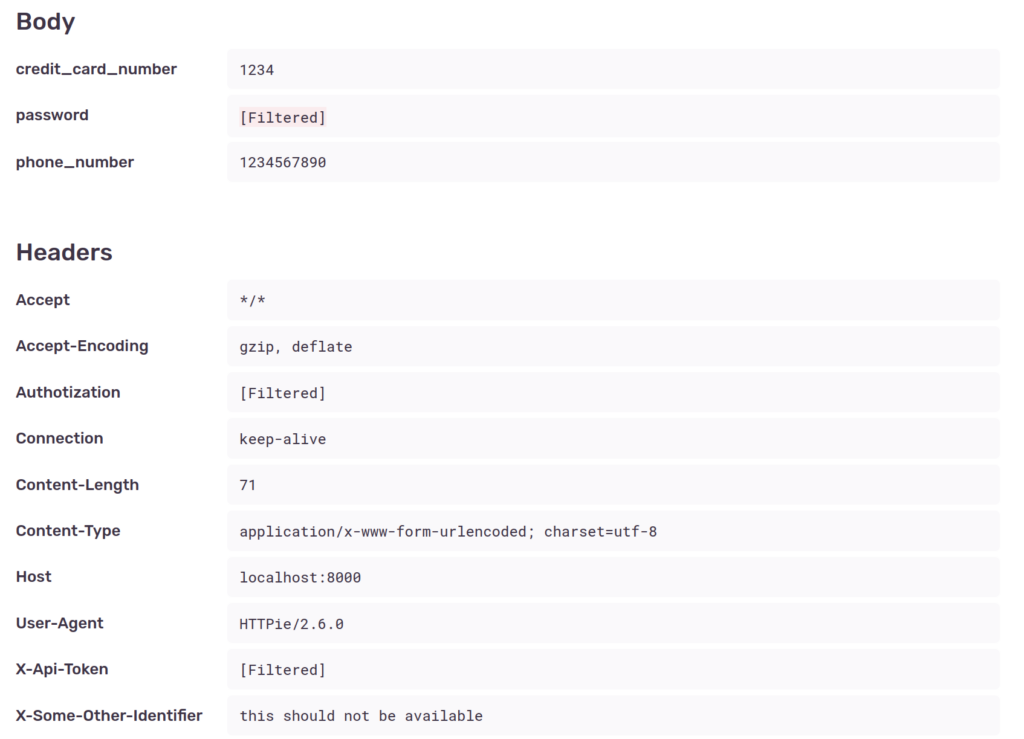

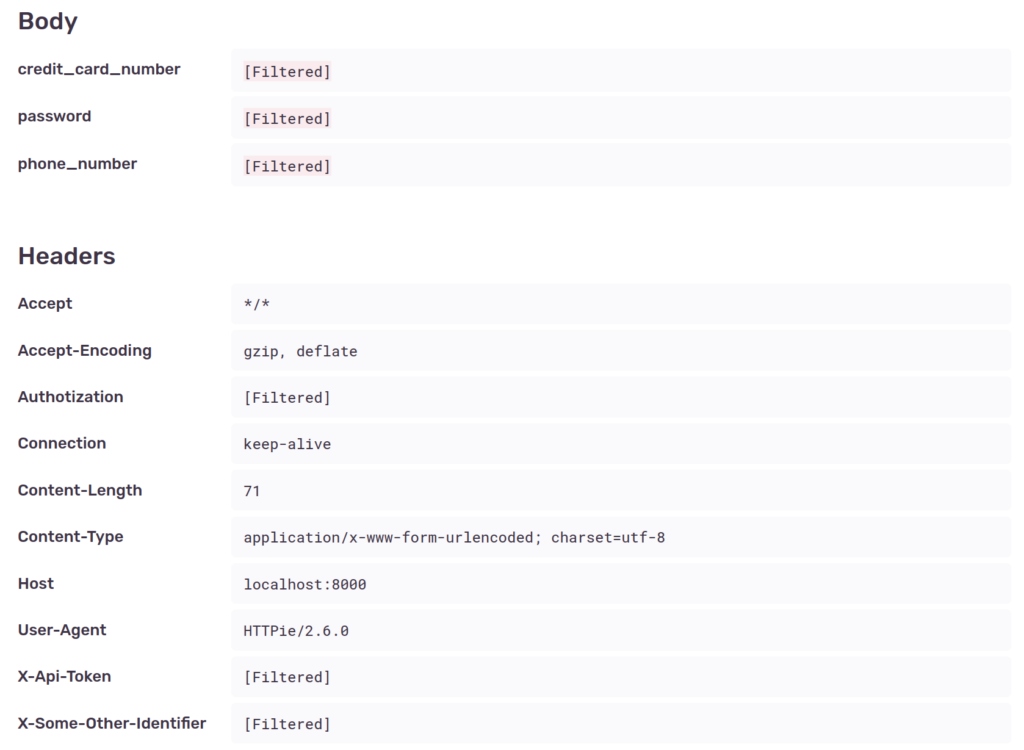

Some sensitive contents of the request such as password, authorization and X-Api-Token are scrubbed from the data, both on local variables and on the shown request data. This is because the SDK’s default deny list checks for the following common items:

['password', 'passwd', 'secret', 'api_key', 'apikey', 'auth', 'credentials', 'mysql_pwd', 'privatekey', 'private_key', 'token', 'ip_address', 'session', 'csrftoken', 'sessionid', 'remote_addr', 'x_csrftoken', 'x_forwarded_for', 'set_cookie', 'cookie', 'authorization', 'x_api_key', 'x_forwarded_for', 'x_real_ip', 'aiohttp_session', 'connect.sid', 'csrf_token', 'csrf', '_csrf', '_csrf_token', 'PHPSESSID', '_session', 'symfony', 'user_session', '_xsrf', 'XSRF-TOKEN']However, other sensitive data is included, such as credit_card_number (assigned to the card variable), phone_number and the X-Some-Other-Identifier header.

To avoid this, we should expand the list:

DENY_LIST = DEFAULT_DENYLIST + [

"credit_card_number",

"phone_number",

"card",

"X-Some-Other-Identifier",

]

sentry_sdk.init(

dsn="<your dsn here>",

send_default_pii=False,

event_scrubber=EventScrubber(denylist=DENY_LIST),

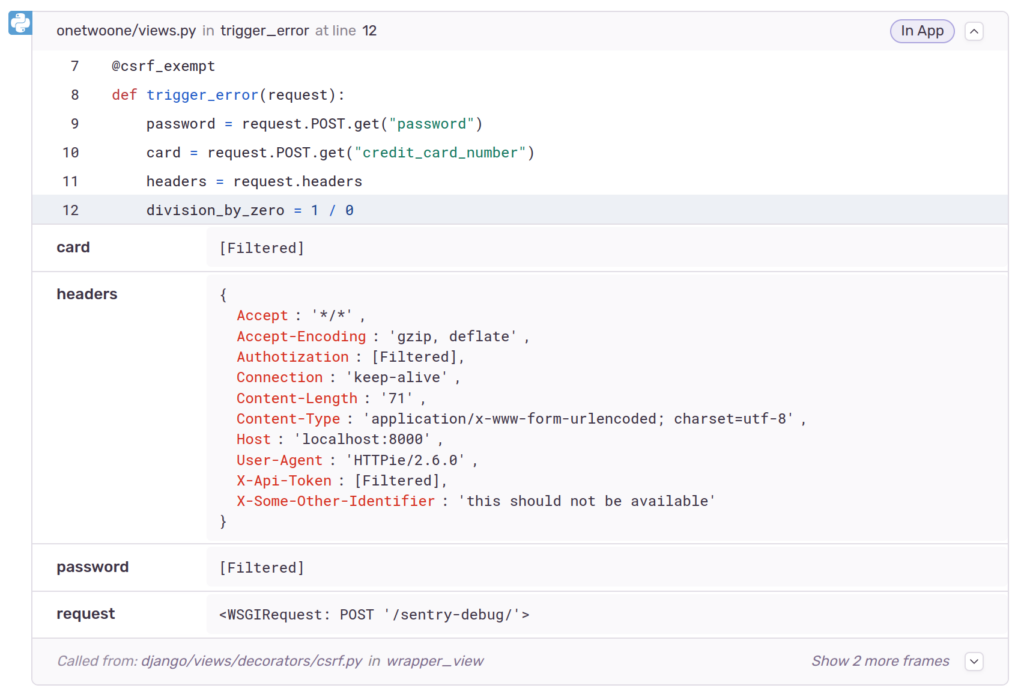

)If we check again, the information is not there for new errors:

This way we achieve our initial goal and just like Django’s decorators we can stop certain information from being included in the error reports.

I still think that a deny list defined in the settings is a poorer experience and more prone to leaks, than the decorator approach used by Django error reporting. Nevertheless, both rely on a deny list, and without being careful, this kind of approach will eventually lead to leaks.

As an example, look again at the last two screenshots. Something was “filtered” in one place, but not in the other. If you find it, please let me know in the comments.